When the storm hits, will your animals survive? A guide to sheltering pets and livestock through collapse

01/23/2026 / By Lance D Johnson

As a historic winter storm barrels across the United States, threatening to paralyze infrastructure from Texas to New York, millions of Americans are bracing for power outages, frozen pipes, and impassable roads. For the countless households that include pets and livestock, this emergency carries an added layer of dread. The silent truth of modern animal husbandry is its deep dependence on invisible, fragile systems. When the electricity fails, the feed store closes, and the veterinarian’s phone rings unanswered, the daily routines that keep animals alive can unravel with alarming speed. True preparedness is not about fear, but about a clear-eyed assessment: if nothing improves and no help arrives, how long can you realistically keep every creature in your care alive? The answer requires planning that goes far beyond extra bags of kibble.

Key points:

- Animal care is a system dependent on constant external inputs like power, fuel, and supply chains; when these fail, crises develop faster than most owners anticipate.

- Evacuation with animals is often a fantasy disrupted by real-world constraints like traffic, animal behavior, and a lack of pet-friendly shelters, making shelter-in-place planning the essential baseline.

- The most critical resources are water and feed, but their management under stress involves calculating for increased consumption, spoilage, and the need for manual redundancy.

- Basic medical care and sanitation become paramount to prevent small issues from cascading into fatal problems when professional help is absent.

- Security risks evolve, as livestock can become targets for theft or predation when normal societal controls break down.

The fantasy of a orderly evacuation with all animals in tow is one of the most persistent and dangerous assumptions. Pets do not evacuate like luggage. Dogs may panic, cats can vanish, and animals that tolerate crates on a calm day may violently refuse them under duress. For livestock owners, the logistics become nearly impossible. Trailers require fuel that may be scarce, roads may be blocked, and destinations are overwhelmingly limited. Most emergency shelters and hotels either refuse animals outright or impose strict limits, with large animals almost never welcome. Planning to evacuate animals should be treated as a secondary, bonus plan. The primary assumption must be the ability to shelter them in place, potentially for weeks, without resupply.

This reality forces a brutal but necessary question from the outset: what are your actual limits? Federal agencies like the USDA and the American Veterinary Medical Association emphasize pre-disaster assessment for a reason. History shows that animals deteriorate faster than people once routine care vanishes. A minor cut can become a systemic infection. A manageable parasite load can cripple an animal when their nutrition drops. Planning ahead means deciding in advance what you can sustain, where your breaking points are, and which animals are prioritized for care when resources become strained. These decisions feel harsh in peacetime but prevent even harsher outcomes made under exhaustion and fear.

The twin pillars: water and feed

In any scenario, two systems demand paramount attention: water and feed. Water is the non-negotiable. Food shortages weaken animals over time, but water failures kill them quickly. The most common single point of failure is the electric pump. Wells, pressure tanks, and automatic waterers all cease functioning when the grid goes down. Hauling water by hand is sustainable for a few pets for a short time, but for livestock, it becomes a physically punishing and ultimately impossible task. The solution lies in redundancy and simplicity. Gravity-fed tanks, large stock tanks that can be manually filled, and open reservoirs are less efficient but far more reliable than complex systems that fail completely.

Feed, while slightly more flexible, is often the first system to break because of miscalculation. People plan for normal consumption, not stress consumption. Animals eat and waste more when routines are disrupted. A month’s supply can vanish in two weeks. Storage is as important as volume; feed ruined by moisture, mold, or pests is worse than none at all. Furthermore, reliance on a single commercial ration is risky. When that bag runs out, animals may refuse unfamiliar alternatives. Successful planning involves diversifying feed sources, using rodent-proof containers, and having a disciplined rationing strategy ready before supplies run low. It is about treating feed as a living system, not a static pile of bags.

When the vet is not an option

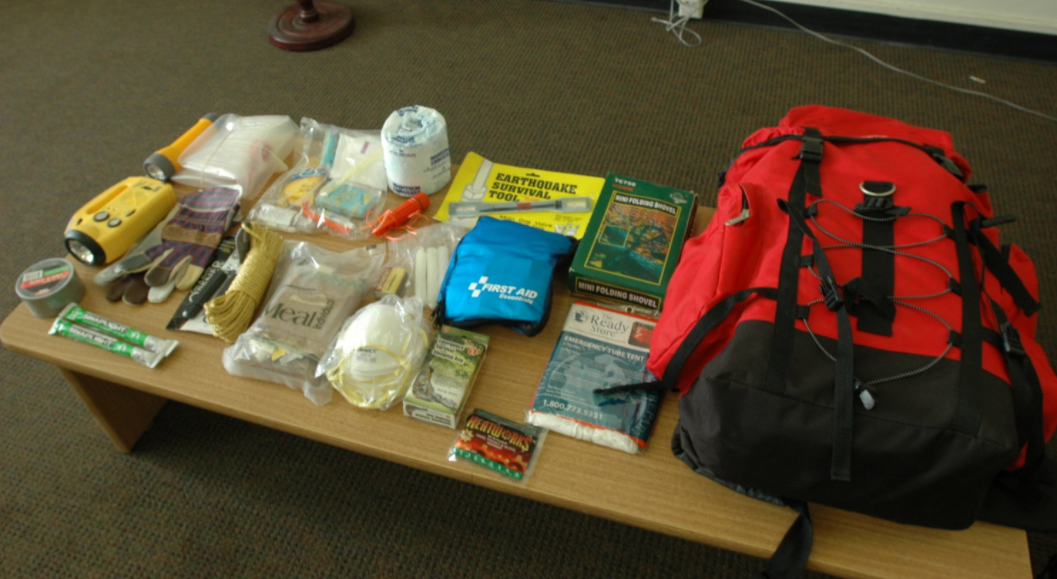

The medical care animals receive during normal times is often a tapestry of routine veterinary support. When that vanishes, optimism becomes a liability. The most common issues are not dramatic injuries but quiet, creeping problems: infections from untreated wounds, exploding parasite loads, digestive issues from stress or changed diets, and respiratory illnesses fueled by poor sanitation. An animal in pain will stop eating, become aggressive, or isolate itself, creating secondary crises. Preparedness here does not mean playing veterinarian. It means having the basic knowledge and supplies to clean wounds, control parasites, monitor for fever, and recognize when an animal’s condition is moving beyond help. A well-organized, dedicated medical kit is crucial. Spreading supplies across general gear guarantees they will be lost when needed most.

The environment around animals also shifts in dangerous ways. Sanitation is the slow, quiet killer that many underestimate. When bedding is scarce and cleaning water seems too precious to use, waste accumulates. This creates a breeding ground for disease and parasites, weakening animals gradually until recovery is a steep climb. Similarly, security risks evolve. Predators, emboldened by reduced human activity, will take more risks. More unsettling is the human element. As historical patterns in disruptions show, livestock can quickly transition from being farm assets to being perceived as unprotected food or valuable currency for desperate people. Security planning shifts from keeping coyotes out to deterring human temptation through locked gates, covered enclosures, and maintained visibility.

Ultimately, disaster planning for animals is about making difficult decisions ahead of time. It is about setting thresholds for how long your resources last and defining which animals are sustainable. True flexibility requires clear limits. Writing these plans down, labeling supplies, and establishing simple routines reduces the cognitive load during a crisis when clear thinking is hardest. The goal is not a perfect outcome or saving every animal at any cost. The goal is to ensure actions align with pre-made, rational decisions, thereby reducing suffering and preserving life for as long as possible. When the storm hits, or the grid fails, the animals in your care will not have the luxury of patience. Their survival will depend on the systems you built and the choices you made long before the first snowflake fell.

Checklist for preparation

1. Identification & Documentation:

- Ensure all animals have permanent, up-to-date identification (microchip, tattoo, leg band).

- Create and waterproof an “animal passport” for each: recent photo, ID numbers, medical records (vaccinations, allergies), behavioral notes, and proof of ownership.

- Keep digital copies in a cloud service and physical copies in your go-bag and home safe.

2. Emergency Medical Care & Supplies:

- Skill Acquisition: Take a basic pet/livestock first aid and CPR course.

- Build Kits: Assemble species-specific first aid kits (include wound care, antiseptics, bandages, vet-wrap, thermometer, tweezers, scissors, animal-safe pain relievers as prescribed by your vet).

- Medication Stockpile: Maintain a rotating supply of any prescription medications, preventatives (flea/tick, heartworm), and dewormers. Discuss emergency dispensing with your veterinarian.

- Resource: Acquire a comprehensive animal first aid manual and keep it with your kits.

3. Sustained Food & Water Security:

- Stockpile: Maintain a rotating, airtight storage of at least 2-4 weeks of food per animal. For livestock, calculate and store feed/hay for an extended period.

- Water Planning: Store a minimum of 2 weeks of water (1 gallon per day for a medium dog, adjust for species/size). Have portable water filters/purifiers capable of processing water for animals.

- Non-Electric Feeding/Watering: Have collapsible bowls, buckets, and non-spill containers. For poultry/livestock, have backup water troughs and feed bins that don’t rely on automatic systems.

4. Shelter & Safe Containment:

- Evacuation: Have sturdy, labeled carriers/crates for each small pet and a plan for larger animals (halters, leads, horse trailers). Practice loading quickly.

- Shelter-in-Place: Reinforce housing (coops, barns, kennels) for severe weather. Plan for bringing outdoor animals inside if needed. Have materials (tarps, spare lumber) for quick repairs.

- Security: Ensure all fencing, pens, and gates are in excellent repair. Have backup tie-outs, leads, and cable runs. Plan for predator deterrence without grid power.

5. Sanitation & Waste Management:

- Stockpile essentials: litter, litter boxes, poop bags, disinfectants (animal-safe like bleach diluted 1:32), trash bags, shavings, and mucking tools.

- Have a plan for managing large volumes of manure/waste if municipal services are down.

6. Home Chemistry & Equipment Maintenance for Animal Care:

- Learn Basic Skills: Understand how to safely dilute disinfectants, create saline solution, and use natural antiseptics (like honey for certain wounds).

- Maintain Equipment: Learn to manually sharpen hoof trimmers, shears, and grooming tools. Service and have spare parts for critical non-electric equipment (hand milkers, manual clippers).

- Water Purification: Know how to use and maintain chemical water treatments (e.g., iodine tablets, chlorine dioxide) and filters for animal water.

7. Breeding & Population Management:

- Have a clear plan for managing intact animals to prevent uncontrolled breeding during a long-term event.

- Stockpile necessary supplies for birthing if you intentionally breed (whelping/kidding kits, heat lamps with safe, alternative power).

8. Training & Behavioral Preparedness:

- Train Animals: Ensure dogs have reliable recall and are crate-trained. Livestock should be halter-trained and comfortable being handled and loaded.

- Desensitization: Acclimate animals to travel in carriers, wear boots/muzzles, and experience simulated stressful scenarios (crowded spaces, loud noises) calmly.

9. Community & Legal Planning:

- Network: Identify neighbors, friends, or local farms for mutual aid (animal shelter, resource sharing, evacuation help).

- Research: Know which local emergency shelters accept pets and their requirements. Have a list of pet-friendly hotels/vet clinics outside your immediate area.

- Legal: Post visible “Pets Inside” rescue stickers on your home’s entrances. Have a designated caregiver in your will/power of attorney documents.

10. Species-Specific Considerations:

- Poultry: Have a secure, movable coop for protection. Plan for feed storage that is rodent-proof.

- Rabbits/Herbivores: Secure a long-term source of hay/greens. Understand forage safety.

- Horses/Livestock: Have hard copies of maps to evacuation routes and pre-identified secondary holding pastures. Maintain hoof-trimming tools and knowledge.

By systematically accomplishing these tasks, you extend your resilience to your entire household—ensuring your animals are a managed asset, not a liability, during a grid-down scenario.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

animal health, animal preparedness, disaster planning, disaster response, emergency kits, emergency shelter, feed storage, food security, Gear, homesteading, infrastructure failure, livestock management, offgrid, pet safety, predator control, preparedness, rural safety, sanitation, self-reliance, survival, survival planning, veterinary care, water security, winter storm

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

FoodStorage.News is a fact-based public education website published by Food Storage News Features, LLC.

All content copyright © 2018 by Food Storage News Features, LLC.

Contact Us with Tips or Corrections

All trademarks, registered trademarks and servicemarks mentioned on this site are the property of their respective owners.